Retiring can be a very stressful stage for many people. Daily routines, life purpose, and long-term goals, all come to an inflection point at once. The recent downturn in the financial markets has added an extra layer of unknowns to an already difficult time for those going through retirement. Having a clear perspective about the impact an economic cycle has on your retirement portfolio can help bring some much-needed clarity.

The curated article below “The Tricky Math of Retiring Into a Downturn” by Tara Siegel Bernard, provides some useful context, and proposes valuable tips to stay ahead of these financial market setbacks even through retirement.

Source: The Tricky Math of Retiring Into a Downturn The New York Times, August 11th, 2022

The Tricky Math of Retiring Into a Downturn

Market declines during the first five years of retirement can have a significant effect on a financial portfolio, but remaining flexible can mitigate the damage.

By Tara Siegel Bernard

Most Americans finance their retirement with a certain amount of faith: Investing will help their savings keep pace with inflation, institutions will continue to work as they always have, it will all work out in the end.

It’s challenging to maintain that optimism in moments like these, when it seems just about everything is at stake nothing is certain. You could call the American approach to retirement gambling, and you wouldn’t be wrong.

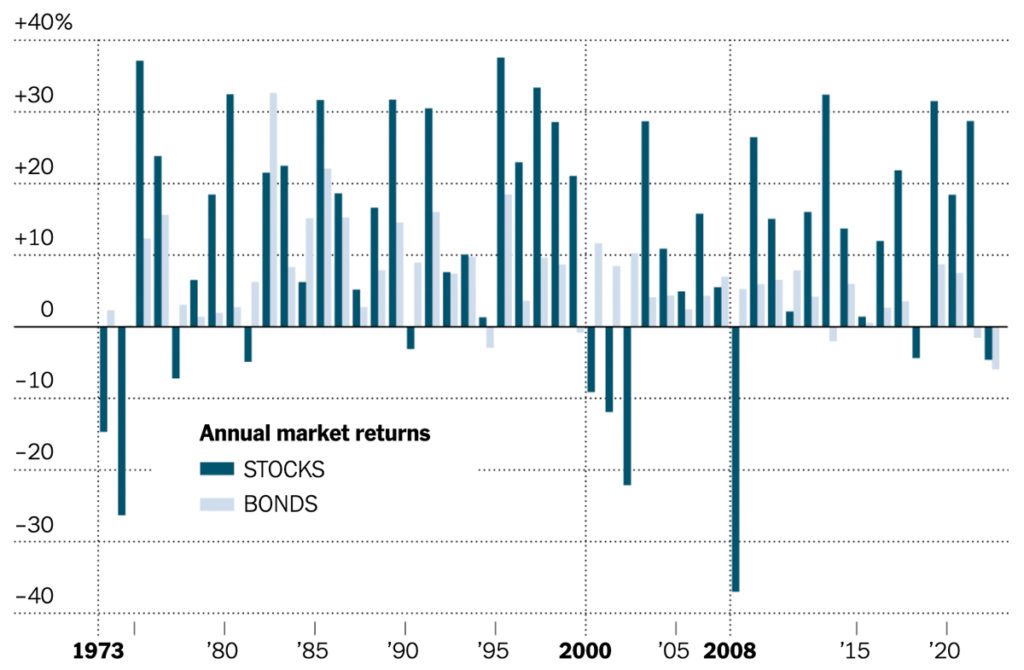

Of course the future has always been uncertain. It was unknowable in 1973, during one of the highest-inflation periods; in 2000, when the dot-com bubble burst; and again in 2008, when the housing and financial markets collapsed. And it’s opaque now, when the markets are down about 11.6 percent year to date while inflation remains high, at 8.5 percent in July, though it slowed slightly from the previous month. Bonds usually provide some cushion when stocks plummet, but they haven’t provided much of a buffer, either.

“This year has been unnerving for retirees because it has been a triple whammy — falling stock prices, falling bond prices and high inflation,” said Christine Benz, director of personal finance and retirement planning at Morningstar.

Unlike younger workers, retirees don’t have the luxury of waiting it out. Timing matters. Market declines that occur during the first five years of retirement can do significant and permanent damage, making it more likely a portfolio will be depleted — largely because there’s less money left intact for when the market (eventually) recovers. It’s less risky to experience such a decline further into retirement simply because the money no longer has to last quite as long.

T. Rowe Price recently peered into the past half-century to see how people who retired into different downturns fared, even in periods of high inflation. The good news: Their portfolios performed well, or are expected to. The less good: Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

The firm’s research is rooted in the widely known 4 percent rule of thumb, which found that retirees who withdrew 4 percent of their retirement portfolio balance in the first year, and then adjusted that dollar amount for inflation each year thereafter, created a paycheck that lasted 30 years.

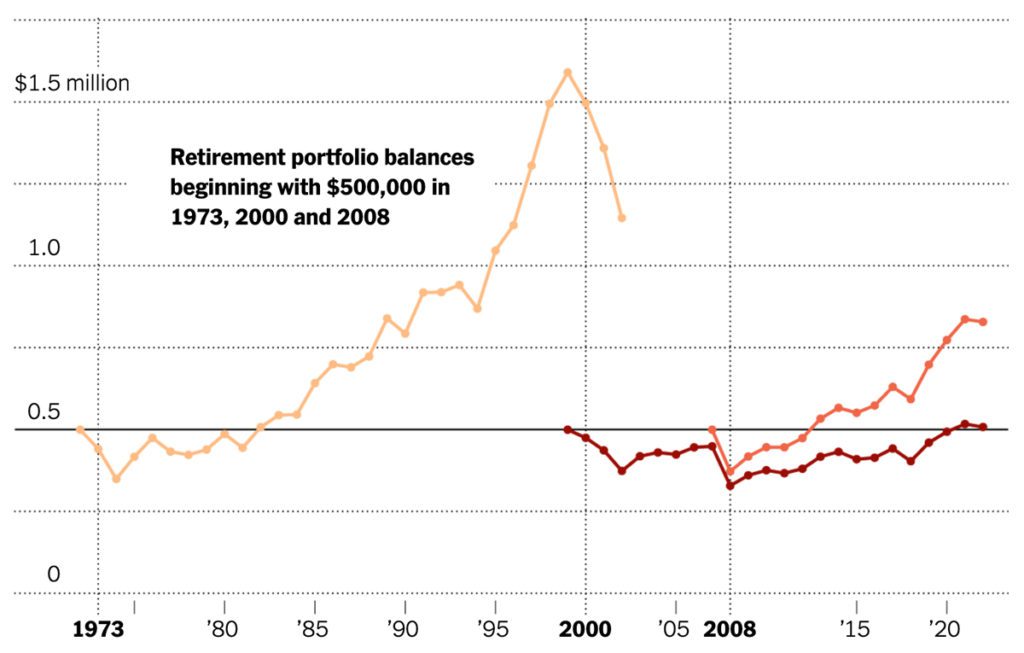

Using that framework, T. Rowe Price analyzed how investors with a $500,000 portfolio — 60 percent stocks and 40 percent bonds — would fare over 30 years had they retired at the beginning of the year in 1973, 2000 and 2008. (The latter two periods are still running.) They would all start withdrawing $1,667 each month — or $20,000 annually — and then increase that amount each year by the previous year’s actual inflation rate.

Let’s rewind to 1973, which, given the oil embargo and high inflation rates, echoes the present. Retirees then would have had to watch their portfolios shrink to $328,000, or nearly 35 percent, by September 1974, and inflation rise by more than 12 percent by the end of the same year, the analysis found. An incredibly painful one-two punch.

The retirees had no idea at the time that circumstances would turn around, but within a decade into retirement, the portfolio balance had reached $500,000 again. And even after the downturn of 2000, at the end of 30 years, the portfolio had soared to well over $1 million.

“It all kind of pins on starting out with that 4 percent withdrawal rate,” said Judith Ward, a senior financial planner and thought leadership director at T. Rowe Price.

Timing Matters More When Retiring

The portfolio of a person who retired in 1973 most likely performed better than the portfolios of those who retired in 2000 or 2008.

Notes: Stocks are the S&P 500; bonds are the Bloomberg Barclays U.S. Aggregate Bond Index. Retirement portfolio balance assumes an asset allocation of 60 percent stocks and 40 percent bonds and a withdrawal amount of 4 percent in the initial year and thereafter adjusted for inflation.By Karl Russell

She conceded that retirees don’t actually spend in straight lines, and that they tend to spend more earlier in retirement. But the study, she said, underscores the importance of starting with a conservative spending plan when a portfolio is down. “That lever of how much you are spending is really a strong lever that works,” she added.

Using the same approach with those who retired into more recent bear markets — in the periods after 2000 and 2008, when the stock market lost roughly half its value — the portfolios were also projected to be sustainable, even though retirees still have roughly eight and 14 years to go before they hit 30 years of retirement. (Ms. Ward’s conclusions also held for other scenarios, including one in which inflation persisted at 9 percent for the remainder of the 30-year retirement periods.)

“These scenarios assume the investor didn’t adjust their behavior due to the inevitable anxiety steep market losses likely caused,” Ms. Ward said. “It’s human nature to adapt and adjust, and retirees would likely want to modify their plans in some way.” That adds an even stronger margin of safety, she said.

Other experts caution retirees not to take too much comfort in the past results because the future — always uncertain! — may have something else in store.

“Using the past provides false confidence,” said David Blanchett, head of retirement research at PGIM, the asset management firm part of Prudential Financial. “The U.S. and Australia have had two of the best capital markets over the past 100 years. That is useful, but you have to look forward.”

That’s why financial experts suggest taking a flexible approach to withdrawals, focusing on what you can control in that moment as conditions change.

Here are some strategies that may help.

Reframing. One approach is to think about your withdrawals in terms of needs, wants and wishes. How much of your basic needs are covered by predictable sources of income like Social Security or pensions, and how much more do you need to withdraw to cover the remainder? Maybe the withdrawal rate to cover your basics is 3 to 4 percent, but your wants might be somewhere from 4 to 6 percent. “The most important thing is to have your needs covered,” Mr. Blanchett said.

A cash bucket. The big idea here is to keep at least a year’s worth of basic expenses — not covered by predictable income sources, like Social Security — in cash or something equivalent, so that retirees experiencing a downturn can spend out of this bucket instead of having to touch their portfolio, giving it more time to recover.

This approach requires some planning, but it can ease anxiety for retirees who find comfort in compartmentalization. Critics have said keeping a meaningful amount of a portfolio in cash may pose a drag, hurting returns over the long run, but for many retirees it may provide a plan they can stick with — and that’s the most important factor.

Guardrails. This strategy, created by the financial planner Jonathan Guyton and the computer scientist William Klinger, encourages retirees to be flexible, increasing their withdrawals when the market is doing well and pulling back when it’s not.

Their research found that retirees are usually safe starting out with a withdrawal rate of roughly 5 percent for the first year (then adjusting that amount up each year for inflation) — as long as they cut back when they receive a warning signal.

That warning light starts blinking when the withdrawal rate increases a certain amount — or one-fifth — above its initial rate. So if the portfolio plummets and the amount withdrawn now translates into 6 percent or more, up from 5 percent, retirees would need to cut their withdrawal dollar amount by 10 percent.

For example, consider a retiree who in the first year collects 5 percent, or $25,000, from a $500,000 portfolio. If inflation was 9 percent, the next year’s withdrawal would normally rise to $27,250. But if a guardrail was tripped — that is, if the portfolio plummeted to roughly $415,000, making that $25,000 now equivalent to a 6 percent withdrawal rate — the amount withdrawn would instead need to decline to $24,525 (or 10 percent less than $27,250).

Conversely, if the portfolio grows, causing the withdrawal rate to shrink to 4 percent, the retiree can increase the dollar amount withdrawn by 10 percent and adjust for inflation thereafter.

This rule is generally applied until the final 15 years of retirement — for example, an 85-year-old couple who want to be safe until age 100 can stop using it, as long as they aren’t concerned about how much money they want to leave to their heirs.

Check up. This is another rough rule of thumb that helps retirees figure out whether they may be withdrawing too much.

Let’s say you’re retiring at 70 and you decide you will probably need your money to last until age 95. Divide one by 25 (the number of years you need the money to last): That translates into a 4 percent withdrawal rate for that year. With a $500,000 portfolio, that’s $20,000.

But if you’re on track to pull out $30,000 that year — or 6 percent — you may want to pull back. “It’s an ongoing gut check,” Mr. Blanchett said. “Is this going to work long term? And that is a really simple way to get an answer.”

And if you don’t adjust? Just understand that you may have to make more drastic changes later.

“You are just trading money with yourself over time,” Mr. Blanchett added.

Tara Siegel Bernard covers personal finance. Before joining The Times in 2008, she was deputy managing editor at FiLife, a personal finance website, and an editor at CNBC. She also worked at Dow Jones and contributed regularly to The Wall Street Journal. @tarasbernard