Back in the 1980s, stock picking gurus such as Peter Lynch at Fidelity offered small investors a strikingly simple mantra: “Invest in what you know.”

The idea was intuitive and highly attractive for a number of reasons. Essentially, if you noticed a small coffee chain with a line out the door, you bought that stock. If you worked in the aerospace industry, all the more reason to buy stock in your own firm.

Lynch made his clients a lot of money, of course. But buying what you know wasn’t a winning strategy for all investors. Someone bought stock in an industry that has since ceased to matter. Someone else bought shares in a doughnut shop that didn’t expand like that coffee chain.

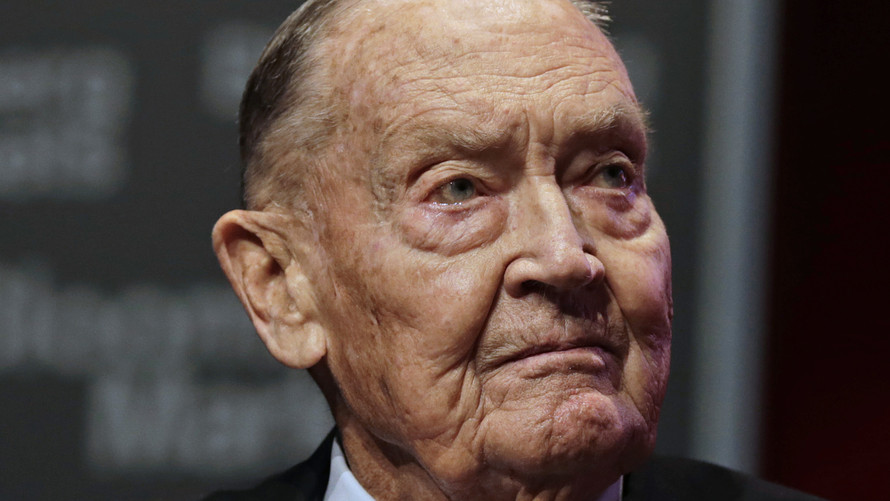

What got me thinking about the example of Lynch is his inverse, the indexing pioneer and Vanguard Group founder John Bogle. Speaking to the CFA Institute in May, Bogle offered a few simple observations on the problem of fund managers.

“Only 57% of equity mutual funds in existence ten years ago survived the decade. If we extrapolate that failure rate forward for a four-fund portfolio over an investment lifetime of, say, 60 years, we would expect the client to experience ten fund failures,” Bogle said.

What Bogle is saying amounts to a plain English explanation of survivorship bias, the tactic among fund companies of burying their dead by dissolving funds that fail.

Like Lynch picking Starbucks, the assumption is that every big winner will win by enough to wipe out the scores of losers. Lynch called a great stock a “10 bagger,” meaning a stock that increases tenfold in value while you own it.

Left unsaid is the effect of even a single “negative 10 bagger” that results in a major, unrecoverable loss.

Mutual funds are supposed to fix this problem by providing diversification. If an actively managed fund owns 50 or 100 stocks, the presumption is that there will be more winners than losers, and that chasing the winners higher and cutting losses on the losers will result in better overall returns, year after year.

Except, of course, that the facts often don’t support the fantasy. Most active mutual funds lag the indexes they track, especially after fees. Survivorship bias allows fund companies to claim genius-level talent that doesn’t exist.

Sobering risk

Bogle again: “Take into consideration the average tenure of active fund managers. The asset-weighted average tenure of active equity fund managers is just under nine years. Again, extrapolating that past experience, an investor with a four-fund portfolio would experience 27 manager changes over the next 60 years. After all those fund failures and manager changes, to say nothing of the onerous annual costs, what are the chances that such a client would even come close to matching the return of the S&P 500?”

The short answer is, not close at all. S&P Dow Jones Indices tracked thousands of funds over 15 years and concluded that actively managed funds — large-cap, mid-cap or small-cap — trailed the benchmarks, year after year.

An S&P analyst concluded from the data that fee collecting by active managers is doomed. Her charitable conclusion is that active managers will find other ways to add value, perhaps by investing quite differently than the index itself.

Which just brings up the sobering prospect of risk. Who wants to pay a price, any price, to take a higher than necessary risk? If you think your fund manager is the second coming of Peter Lynch, perhaps. But most are not.

“The solution seems too obvious to explain,” Bogle told the CFA audience. “We are in a new era of professional investing, one in which the rules of best practice are gradually changing. None of us in this profession — no matter what we believe the optimal investment strategy — can ignore the importance of costs, of indexing and of long-term focus.”