The reason “bond king” Bill Gross was destined to depart from his own company, Pimco, isn’t so hard to understand. His Total Return fund had some good years and some great years, sucked in hundreds of billions in assets and got very, very big.

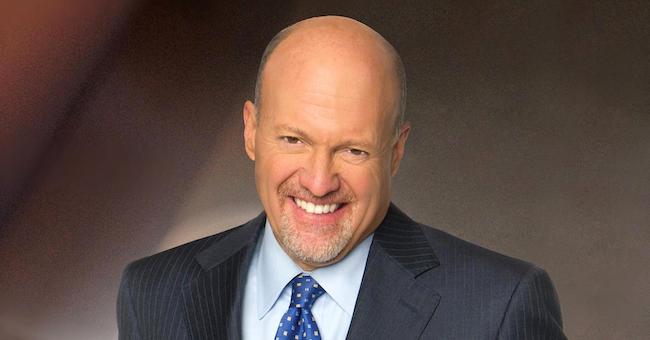

Bigger than the economies of developed countries kind of big. As Jim Cramer, the CNBC host, predicted just a month ago, big mutual funds are their own worst enemies. Once they get large enough, they nearly always start to underperform.

Eventually, Gross couldn’t beat the market because he was the market. His every trade was in the billions, soaking up all the liquidity and moving against him. He effectively became an index fund, albeit one that charged hefty fees and, in time, was doomed to make money-losing calls.

Always willing to talk his book, Gross over the past few years loudly proclaimed the market wrong on several occasions and took contrarian positions against U.S. Treasuries. He fought the market (and the Fed) and it didn’t work out. Like an escape artist trapped in a straitjacket, the more he struggled the tighter it got.

Gross left Pimco this week and started work at Janus, a fund company where he will manage $13 million to start. Pimco manages $2 trillion in comparison, including nearly $290 billion in the Pimco Total Return fund at its peak. Basically, he jumped off the Queen Mary and into a rowboat.

Jeff Gundlach, a competitor who runs rival DoubleLine Capital, echoed Cramer’s assessment this way. Commenting on the move by Gross to Janus, Gundlach told CNBC: “It is the right thing. He can be the head guy at Janus. He can create his own image. Now he can perform better because he isn’t managing a lot of money.”

As an investor, you have to think about this problem. A big fund can’t beat the market because it is the market. Nevertheless, none of these guys works for free. Their fees are tremendous, and that’s real money that leaves their clients’ accounts. So why not just own the market for almost nothing with an index fund?

Why not? Because investors hope against hope to get a return that is better than the overall market. What they also hope, without necessarily saying it aloud, is that their money is safe in the hands of these rock-star managers. Too often, though, you can’t have both and very commonly don’t get either. High risk and high fees go hand-in-hand.

For instance, Morningstar won’t rate Gundlach’s work at the $35 billion DoubleLine Total Return fund. It’s too difficult, they say, to get a grip on how much risk he takes to get the return his clients expect.

It probably doesn’t help that Gundlach won’t talk to Morningstar about what he does, either, and hasn’t for a couple of years. And he probably doesn’t care, since a fair amount of the money exiting Pimco is likely to end up in DoubleLine soon enough.

Trading mirage

This matters because so many have bought so heavily into the idea that some managers have the magic touch. That’s the hunger people have for excess return, and it typically ends in tears. How long until a high-risk position in one of Gundlach’s products turns and bites his clients hard? How long until either his fund or the new Gross-led Janus product gets so big it can’t operate without moving the market against its own trades?

And how many hundreds of millions in fees will investors pay to enjoy the risk-soaked mirage of outperformance in a part of their portfolio, bonds, that they think is there to protect them from losses?

If you’re running a hedge fund and decide to buy the services of a bespoke bond manager, and you have a very good idea of what the fund owns and why, and if that level of risk fits your investment policy, great, go for it.

But if you’re trying to build a retirement portfolio that uses diversification and asset allocation to lower volatility, it’s far simpler and more sane to own bond index funds instead. You’ll enjoy a predictable, credible, low-cost return that won’t put your retirement on tenterhooks just because one guy leaves his company in a huff.