Scott Puritz has been around money for most of his 62 years, so he knows something about the subject. He comes from a family of entrepreneurs. He attended Harvard Business School. He loves researching, discussing and creating able enterprises.

The enterprises he’s built include a profitable cake-delivery company in college (it still exists) to one of the biggest data centers in South America.

“I helped bring the cloud to Brazil,” he said.

Puritz’s new thing is low-cost, minimum-risk investing — a philosophy I heartily endorse (along with saving and living beneath your means). But I don’t recommend (or disapprove of) specific funds, stocks or financial advisers for this column.

Puritz and his business partner are putting their financial IQs to work advising middle-income savers how not to blow their nest eggs. They are doing it through a firm called Rebalance that is disrupting the staid world of boutique investing and stock picking by putting (almost) everything in the cloud.

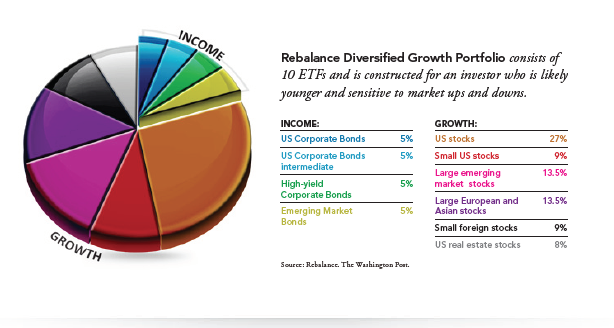

Its conceit is long-term, low-cost indexing, mostly through Vanguard Group’s exchange traded funds (ETF). (I have been a client of Vanguard for decades but do not own an ETF. I have index and managed funds.)

“One of the most shocking things is the low-level financial literacy throughout our culture,” Puritz said. “It’s independent of education. Doctors, MBAs, corporate executives are incredibly competent in everything they do. But when it comes to investing, you run into this cauldron of mostly negative emotions, embarrassment, frustration, guilt. It leads to paralysis.”

Rebalance’s 1,300 clients have total assets of $630 million. The average client has about $571,000 in savings. Rebalance accepts clients with both retirement and taxable savings. It serves a handful of $10 million clients.

Here is how it works: A potential client goes online to schedule a time with a Rebalance financial adviser. In the initial 45-minute consultation, the company asks a series of questions to determine the person’s goals and risk tolerance. The adviser follows up within 24 hours to the prospective client with a recommendation of one of Rebalance’s seven portfolios.

If the person decides, after subsequent conversations, to become a client, the company works with them to consolidate the client’s retirement assets — as painlessly as possible — into one account. At that time, the client pays a one-time $250 fee to Rebalance. Rebalance accepts only clients with at least $100,000 to invest.

Once the client is on board, they can stay in touch with the Rebalance team as often as they like. Once a client is married to a specific fund, that investment is on autopilot until the annual checkup that each client receives. Clients can also get in touch by telephone.

“Our front-line people are financial therapists,” Puritz said. “They need to be empathetic. People are very emotional about their money.”

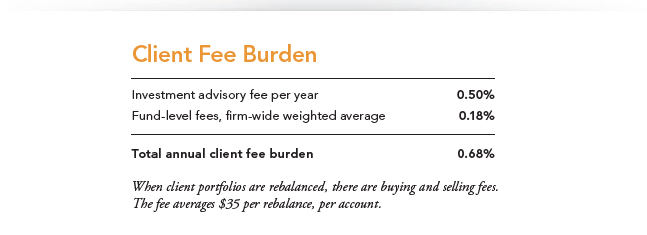

Puritz said he and his business partner, Mitch Tuchman, charge a 0.50 percent fee on total assets, which is deducted from their accounts on a quarterly basis, a standard industry practice.

That means a $100,000 savings pot will cost you $500 a year for their expertise. But that’s not all. There are fees on the ETFs that average less than 0.20 percent that are included in the price of the index fund, which is also standard industry practice.

There are also a couple of modest transaction fees during the year that come to about $70 total. Those fees — as well as the name Rebalance — come from the twice-a-year fine-tuning of the portfolio to ensure its percentages stay consistent with the client’s stomach for risk.

That means that for a $100,000 account, the all-in annual cost averages a bit less than $800.

Here’s what my wife and I do: We have a financial adviser who charges an annual flat fee. The service is different from Rebalance, which sticks only to investing. Our adviser offers broader advice on things such as mortgages, insurance, employee benefits, long-term care and taxes. But he visits us twice a year, and presents a list of our holdings and whether the percentages are in line with our own risk tolerance, similar to what Rebalance does.

Puritz and his partner make money. The firm has 20 employees, earns around $3 million a year in revenue, and is co-anchored in Bethesda and in Palo Alto, Calif., where co-founder Tuchman, a contributor to digital site MarketWatch, lives. Puritz lives in Montgomery County.

The two Harvard graduates have signed up three brand names from the investment world to sit on their investment committee, adding gravitas, expertise and marketing value.

The committee includes Burton Malkiel (“A Random Walk Down Wall Street”) and Charles Ellis (“Winning the Loser’s Game”), considered two of the “godfathers” of indexing investment. It also includes Jay Vivian, who oversaw $100 billion in investments as managing director of IBM’s Retirement Funds. Each has an ownership stake in Rebalance for their efforts.

“Rebalance is consistent with everything that I have believed throughout my professional life,” Malkiel said in a phone interview. “I was the guy in 1973 who said you’d be much better off with an index fund.”

Puritz and Tuchman have used technology right from the start, spending a year working with Salesforce.com to build a cloud-based business platform that put everything, you guessed it, in the cloud. They have eliminated paper and the administrative costs that go with it. Many of Rebalances advisers are men and women who left finance careers to raise children.

For the most part, “there is no ‘mommy track’ in personal finance,” Puritz said. “You find real, high-quality men and women who left the finance business and started families. We found if we can offer them part-time, flexible hours, we can get some very high-quality advisers.”

Its niche is people ages 45 to 65 with about $450,000 to $1 million in investable assets. That’s too small for many traditional wealth advisers, but it fits nicely with Rebalance.

“That’s our sweet spot,” Puritz said, adding that the company was profitable a year after it was started in 2012.

Puritz’s father and grandfather were both businessmen. His grandfather owned a high-end women’s store in Ridgewood, N.J., and his father followed in his footsteps, sort of, founding a successful, high-end men’s clothing store.

“I always thought I was going to be entrepreneurial,” said Puritz, 62. He traces it to “watching my grandfather and my father, and my mother, who started her own real estate brokerage.”

Puritz attended Tufts University, where after only a few months he launched a “snack pak” business allowing parents to send their kids candy and stuff to power them through their first exams. He persuaded the administration to give him a mailing list of home addresses and then sent them letters just before Thanksgiving.

“I made thousands of dollars,” he said.

He launched a similar business based on birthday cakes, working out a wholesale deal with a local bakery and delivering the cakes around campus himself. He sold that for several thousand dollars, and has been building businesses ever since.

He made his money disrupting South America’s traditional telephone business. The United States had been a few years ahead of Latin America in the dissolution of traditional, analog communications in favor of wireless and fiber-optic systems.

Puritz had a window into the industry from some consulting work he had done after Harvard, and saw vacuums that could be filled with new products. He did it with names such as Radio Movil Digital, Diveo and OptiGlobe, which brought the first data centers to Buenos Aires.

By 2002, he was finished and living on his telecom profits in Montgomery County.

Tuchman had a long career in finance and investing, and he and Puritz occasionally jawed about starting a business together starting back in business school.

About 15 years ago, Tuchman had a payday from a Silicon Valley company that had what the venture capital set refers to as a “liquidity event.”

Tuchman wanted to invest money on behalf of his family. He immersed himself in the world of modern portfolio theory, as practiced by Malkiel, Ellis and others.

Tuchman launched MarketRiders, the first online “robo” investing tool. He soon began strategizing with Puritz, and saw broader business possibilities. They joined forces and launched Rebalance to concentrate on investing for others.

“I said, ‘Mitch, this is a great business,’ ” Puritz recalled.

They had a handshake deal by January 2012, but there were challenges. The money management field was hugely competitive. How do we set ourselves apart?

Tuchman wrote an email to Ellis, and the investment icon was receptive to participating.

Tuchman jumped on the Amtrak train in Washington, and met Ellis for breakfast the next day. This led to Malkiel and to Vivian. And a business was born.

Thomas Heath is a local business reporter and columnist, writing about entrepreneurs and various companies big and small in the Washington metropolitan area. Previously, he wrote about the business of sports for The Washington Post’s sports section for most of a decade.

This article was originally published in The Washington Post on July 6, 2018.