Quick question: What title does your financial advisor use? What’s actually on his or her business card?

If the words are “financial advisor,” the feds could come calling with pointed questions.

The problem is one of legal responsibility. In the final weeks of the Obama administration the government was set to raise the bar on the quality of your financial advising.

Specifically, the Department of Labor planned to enact the fiduciary rule, a change in the law that would make it very hard for commissioned financial salespeople such as stock brokers and annuity sellers to pretend to be true, unconflicted advisors.

The rule was partially enacted in June last year, though the Trump administration has slowed the law’s rollout.

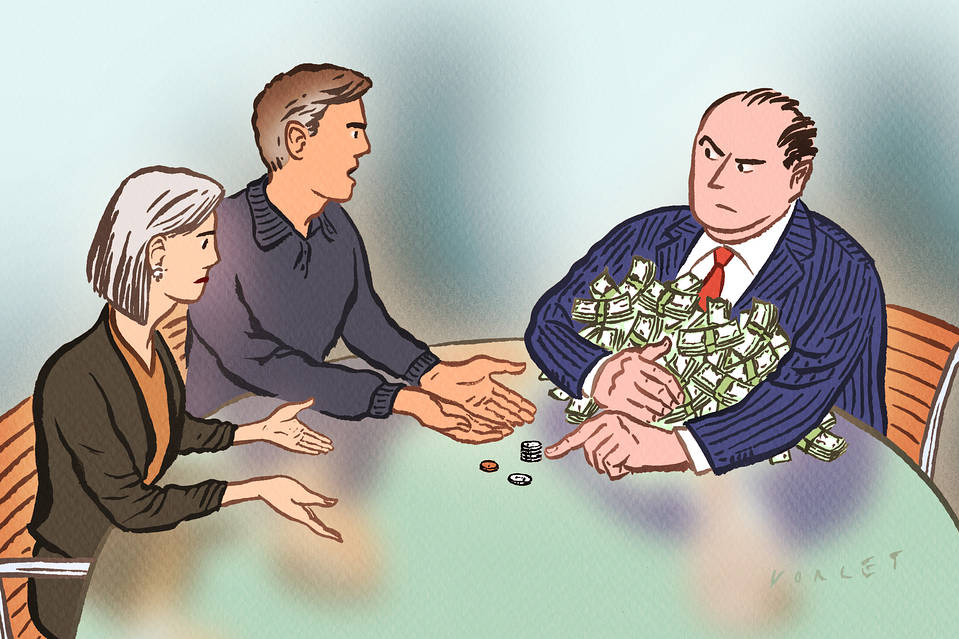

The difference between broker and an advisor is huge. A broker is only required to sell you investments that are “suitable” for your goals. Even if he pockets a fat, virtually undisclosed commission on the side.

The ugly truth is, that’s how commissioned salespeople make money. They get paid by mutual funds and insurance companies to “move product.”

A true financial advisor is held to a higher standard — he has to reveal any potential conflicts of interest and must by law act in your interest first, ahead of his own.

Now the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) is moving to bar stock brokers and annuity sellers from masquerading as financial advisors. New rules on titles could be voted on in the second quarter of this year.

“You can’t do this unless you get to the substance of what the labels mean, and we have to get to the substance of what the labels mean,” Federal Reserve Chairman Jay Powell said recently.

It’s a big deal because for many years the SEC complained that moves by the Department of Labor toward regulating advisors infringed on its jurisdiction.

Fine, shot back fiduciary advocates, then do your job.

Then the whole thing ground to halt when the Trump administration took charge, although some states are beginning to enforce the rules on the books.

Comprehensive change

What’s really interesting, though, is that the SEC action would affect far more of the market than the current rules from the Department of Labor.

The fiduciary rule as its written affects only retirement plans run by employers and Individual Retirement Arrangements (IRAs).

That’s a big chunk of American investments, some $16.3 trillion, but the rule doesn’t affect non-retirement investments. A McKinsey report put that total in the United States at $44 trillion.

Rather than putting just retirement advisors on the hook, anyone who offers investment advice would have to admit to what they are — conflicted sellers of investments who are paid by the very providers of those products.

Or, instead, they can choose to adopt the rules a fiduciary must follow.

You could look at the SEC discussion as an attempt to claw back authority from the Department of Labor while doing very little by going after titles most people don’t understand.

Interestingly, however, a Republican member of the commission is promising that job titles are just the start. “We are working on coming out with a comprehensive proposal,” SEC Commissioner Michael Piwowar told reporters at the same event where Clayton spoke.

Stay tuned.