Walk down the aisles of your local grocery store. If you’ve been shopping for a few decades, you know a few things almost without thinking.

Fresh foods are along the walls, dry goods in the center aisles. Store brands are usually just fine and cheaper.

Now look at the shelves. Some products (say, fancy ground coffee) are right at eye level. Others are down at your knees or way up high.

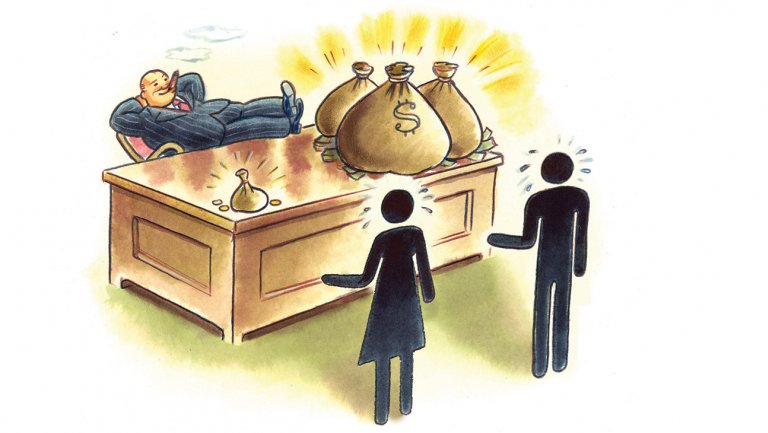

If you suspect that the more costly national brands are closer to where you look first, you’d be right. It’s called “pay to display” and it costs those brands tens of thousands of dollars.

That might be okay with you, if you were disposed to buy a certain Seattle-based coffee brand anyway. But if you are looking for the better deal, get ready to kneel for discounted java.

Nobody is complaining about this because grocery stores don’t owe you an explanation of the real cost of the goods they sell. Financial advisors, if they are fiduciaries, are another matter.

A lot of big banks are anxious to get into the low-cost financial advising game, one built mostly by advisors well outside of the Wall Street world.

So they’re stocking up on cheaper, index-style funds. What’s less obvious, according to Bloomberg News, is how much those funds pay to get in front of new customers — investors like you.

Banks such as Morgan Stanley, Bank of America and Wells Fargo receive financial support from funds, facts which they disclose to clients.

The problem is that “pay to display” means funds that are cheaper to own are not promoted to clients and, in some cases, dropped entirely.

Tellingly, Vanguard Group declined to take part in such promotional schemes. Morgan Stanley then dropped Vanguard on the ground that clients did not want its funds, Bloomberg reports.

Perhaps they don’t. But it’s impossible to say if Morgan Stanley clients can’t buy them. The discount brand is literally not on the shelf in their store.

As I’ve written recently, Vanguard Founder John Bogle created the first index funds with a single goal in mind — to lower the cost of investing.

Part of the reason index funds are so cheap to own is the lack of marketing and promotion cost around them. Payola, in whatever form it takes, doesn’t serve the client.

Masquerading as a low-cost alternative while building in fixed marketing costs creates a conflict of interest that’s extremely hard to avoid.

Sure, banks can disclose that money changes hands, but that’s not what being a fiduciary is about.

Bogle’s mantra

A true fiduciary discloses all costs, provides reasoning for a given investment choice and offers the client comparable alternatives, even those from which the advisor does not benefit.

Furthermore, a fiduciary acts in the interest of the client and the client alone, working to build trust and a long-term relationship.

This might seem like a given, one to which any money manager firm would subscribe. “Of course we work in your interest!” is what an advisor might say.

But there’s a huge difference between saying that and saying that you are, in fact, a fiduciary. Specifically, there’s a legal difference. Your run-of-the-mill salesperson will stop short of claiming fiduciary status if it’s not true. Try it out!

A true fiduciary can create for clients a solid set of low-cost portfolios that respond to the risks and opportunities of the economy we face today and tomorrow.

Importantly, in our view, those portfolios should follow Bogle’s mantra of low-cost investing and do so without the slightest hint of self-dealing. Their advisers and the firm itself should get absolutely nothing from the fund industry, zilch, zero, nada.

In our view, what matters is low cost and high trust. It’s important to keep both goals in sight.